Run a Marathon

Many people are under the impression that any run is a marathon. By definition, a marathon is 42.195 km (approximately 26 miles). The idea for the modern marathon was inspired by the legend of the ancient Greek messenger Pheidippides who, in 490 B.C., raced from the site of Marathon to Athens (a distance of about 40 kilometres) with the news of a significant Greek victory over an invading army of Persians. After making his announcement, the exhausted messenger collapsed and died. To commemorate his dramatic run, the distance of the marathon at the inaugural Modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 was set at 40 km.

At the 1908 Olympic Games in London, the course was extended, allegedly to accommodate the British royal family. As the story goes, Queen Alexandra requested that the race start on the lawn of Windsor Castle (so the littlest royals could watch from the window of their nursery) and finish in front of the royal box at the Olympic stadium—a distance of 26.2 miles (26 miles and 385 yards). The random boost in mileage ended up sticking and, in 1921, the length for a marathon was formally standardised at 42.195 km (26.2 miles). The Olympic Marathon and any marathon events throughout the world are strictly measured at this distance.

Although running a marathon is no average feat, there exists a misconception that running one is no longer that impressive; that somehow making it through 42.195 km on foot in a morning has become easier than it used to be. Maybe that is because I hear so many people having completed a 5 km run saying they have run a marathon. (You may be hearing my sigh.) A 5 km run is precisely that, a 5 km run. The same with a 10 km run. Even a half marathon is exactly that—half of a marathon, at 21.0975 km. The only run that can be called a marathon is one with a distance of 42.195 km.

In an article published in November 2022 by the Marathon Handbook—an organisation founded with the express purpose of helping people run far—it was concluded that only 0.17% of the world’s population has run a marathon. The research was based on a comprehensive mapping of global running participation carried out by RunRepeat, a renowned group of running fanatics, in 2019. The analysis covered 107.9 million race results from more than 70,000 running events over the course of 22 years (1986 to 2018).

As already mentioned, I grew up competing with two much older brothers, so I had to climb higher, play harder, and go faster than a boy—and an older boy at that—to simply keep up. I was a fit competitor who excelled in multiple sports. But I could not run. Or so I thought.

As a child, if I tried to go for a run, I would be out of breath before the corner. “I can’t run” became a mantra. My husband is the natural runner in the family. Before and soon after we were married, I would kiss him goodbye as he left for his morning run. At events, I would sit at the finish line, waiting for him to come in. Until one day, I looked at the profile of those coming across the line—young, old, thin, fat—and figured I could do it too.

I started out small. I puffed my way through 1 km at a time, slowly increasing to my first 5 km race! I made it up to 10 km and felt very proud of myself. “No, I’ll never do a marathon,” I told myself. “I’m not interested in that.”

One day, in the lead-up to the 2001 marathon in Canberra, Australia, I made what would turn out to be a life-changing decision. Four days before the event, I decided to do the full marathon. (I need to clarify that whilst the decision to run the event was last minute, I had done the necessary training. As a member of the Sydney Striders Running Club, I had struggled through months of long runs with support by my side in the form of other very experienced marathoners.) My husband had already registered for the race and was encouraging me to give it a go. My resolve to keep up with others was likely the final factor that drove me to enter. At the registration desk, surrounded by other competitors, my determination not to be left out gave me the final incentive I needed to complete my registration.

On marathon day, I had the time of my life. Other club members encouraged me along the route. I had no expectations of myself so was happy to take it easy and enjoy the journey. As my race entry was a last-minute decision, very few people knew I was doing it, and I did not feel the pressure I would have felt to perform had all my family and friends been checking my progress. (At that point in time, the activity tracking software Strava did not exist and there was no online live tracking of the event, so no one would have been able to follow my run or see how well I had performed unless I chose to let them know.) Apart from a blister on my baby toe, I had a fabulous day out, finishing in a reasonable, albeit not spectacular, time of 4 hours and 6 minutes.

Only after completing my first marathon, did I realise that I enjoyed the companionship of training with my husband and the thrill of completing something that I found tough. Since then, running has been addictive and anyone meeting me today would not believe that at one time I did not run … that I thought I could not run. Since that first marathon in Canberra, I have completed numerous marathons across Australia, joined 44,000 people from around the world on the Champs Elysée to complete the Paris Marathon, and navigated the cobblestones to complete the Florence Marathon. Regular running has also made me fit enough to be able to do things when the opportunity presented itself, including taking part in the Vancouver Half Marathon and the Banff Half Marathon during an extended trip to Canada.

Have you completed a marathon? If so, kudos to you! If not, is it something you aspire to do? If not, drop it, let go, do not stick it on some list of items that you may never do. But if it is something you would like to do … take action towards that goal. Perhaps join a running group for support. It will take time and effort, but as I found out, it may not be impossible even if you once thought it to be so.

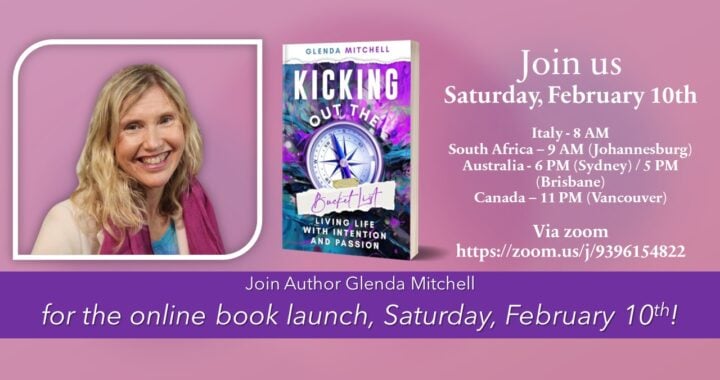

Online Book Launch

Online Book Launch  New Book Release

New Book Release  Book Cover Reveal

Book Cover Reveal  Sneak Preview

Sneak Preview  Imminent Book Release

Imminent Book Release  Lucca 1/2 Marathon

Lucca 1/2 Marathon